1940, the first trip

June 15th, 1940, Charlotte Perriand embarked on the Hakusan Maru from Marseille.

As a reader of Okakura Kakuzo’s famous Book of Tea before her departure, this two-month crossing was an opportunity for her to deepen her knowledge: she said that her meeting with the Japanese ethnologist Narimitsu Matsudaïra gave her a better understanding of the essence of Japanese culture. Upon her arrival, her wonderment did not overshadow her missions. Kitaro Kunii, director of the Industrial Arts Research Institute (IARI), explains them perfectly: “The strategy [of the Japanese government] was to export products of Western and ‘modern’ style, but rethought and reinterpreted according to the criteria of traditional Japanese craft. Within this framework, Perriand’s specific mission was to provide practical advice aimed at improving the design of this craft, to stimulate exports and to ‘identify the best of Japanese industrial art, and propose ways to take advantage of it’.”

After the visit of the German Bruno Taut (1880-1938) for similar reasons, it was Charlotte Perriand’s turn to illuminate Japanese creation with her modern and Western lanterns: with her interpreter and her assistant – future great designer – Sori Yanagi (1915-2011), she fulfilled her missions of criticism and advice around the archipelago: she visited art and design schools, factories, met artists, craftsmen, manufacturers and gave lectures, readings. A game of back and forth takes place: she spread the winds of European modernity into Japanese designers while Japanese objects influence her way of creating.

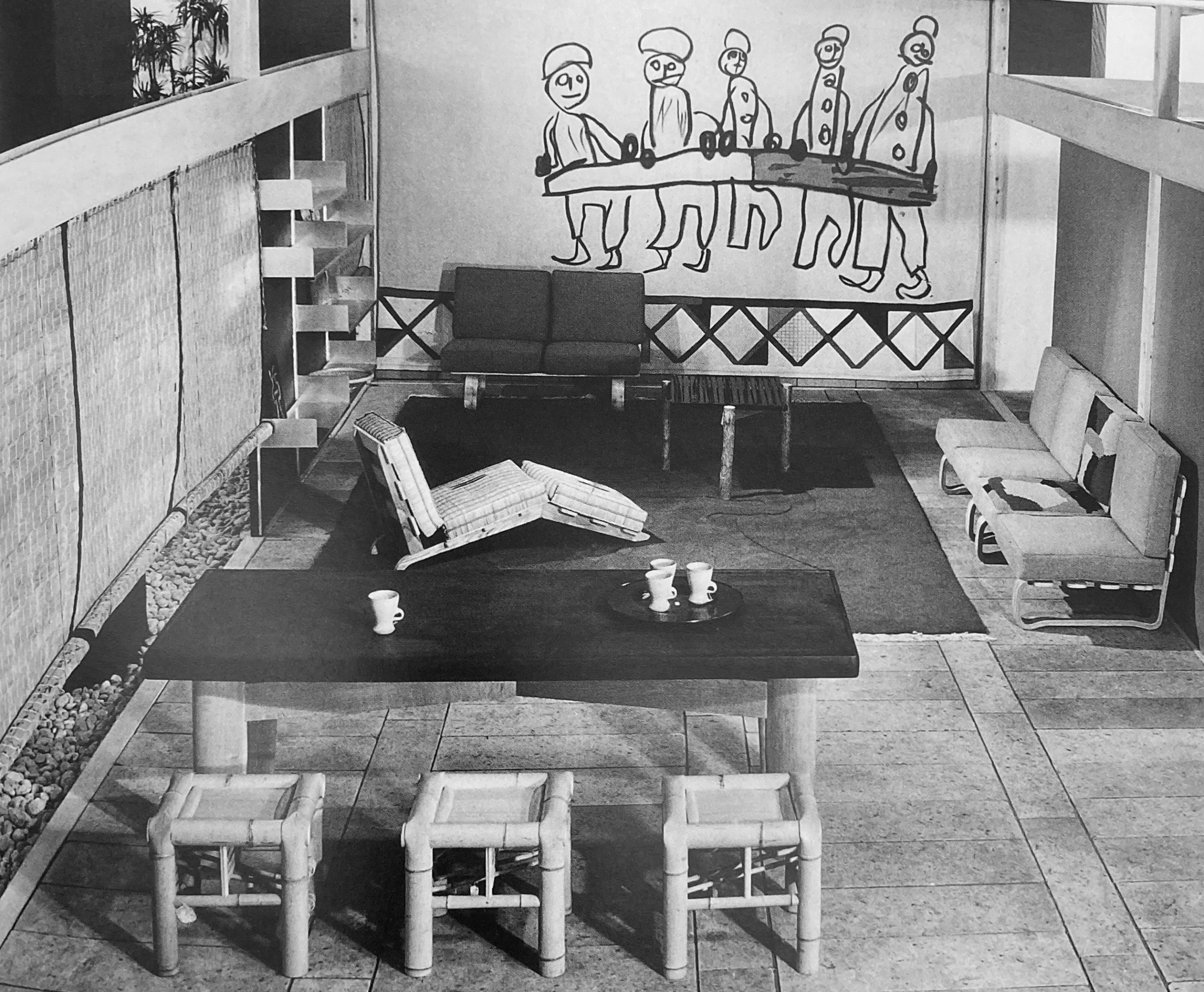

The exhibition “Selection, Tradition, Creation” – from its full name “Contribution to the Interior Equipment of the Home, Japan 2601. Selection, Tradition, Creation” – perfectly reflects these reciprocal exchanges and transformations. First curated at the Takashimaya department store in Tokyo in March 1941, then two months later in Osaka, the exhibition was structured around photographs, Japanese objects and creations that Charlotte Perriand had designed in Japan. A dialogue of mutual emphasis is created: she chose photographs of Japanese objects or the objects themselves already usable and exportable pieces; from the title to the scenography, she disseminates the idea that tradition should be integrated into contemporary creations, without copying it – the subtle mix between tradition and modernity is an essential component of Japanese design. The works Charlotte Perriand exhibits are made with bamboo and rice straw, showing the possibilities of local materials, and how she was inspired not only by Japanese craftsmen as with Ubunji Kidokoro’s bamboo chair, but also more broadly by calligraphy, painting, fabrics and her encounters.

Like an inventory of her visit in Japan, the exhibition highlights her contributions and the way in which the country has marked her: she is fascinated by the deep echoes that exist between traditional Japan and modern architecture, as if the principles that she helped to build at this time already existed in this country that she discovered: the opening of interior spaces to the outside, the use of certain standards (tatami, shoji): in her own words, “practicality and sensitivity form an indissoluble whole in the Japanese soul, intimately linked to its philosophy of things and to its life. […] Japan is, by tradition, the country closest to modern art.”

Shock would be an euphemistic word to describe the effect that Japan had on Charlotte Perriand – and vice versa. However, at the end of her one-year obligation, she became homesick and wanted to return to France. But the escalation of the conflict and the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941 brought Japan into the war and a return via the United States or China was no longer an option for the designer. A troubled period followed and she took refuge in the north of the country: there she wrote one of her major texts in 1942 “Contribution to the interior equipment of the house in Japan”, before succeeding in reaching Hanoi (Vietnam) thanks to the protectorate of the powerful Nishimura family, friend of the Sakakura, before returning to France after some problems.

1955, “Pour une synthèse des arts”

While the first trip bring some foundations and left indelible marks on all the protagonists, her second trip to Japan was not done under the same personal circumstances, nor in the same geopolitical and socio-economic context. Charlotte Perriand’s reputation was established, Reconstruction in Europe embraced functionalist theories, the Korean War broke out in 1950, the international hegemony of the American Way of Life was in full swing, and industry reigned everywhere, including in Japan. Japanese designers were now making the opposite journey to observe Western techniques and technological advances, as Isamu Kenmochi’s (1912-1971) trip to the United States in 1952 proves it; the same year Japan regained its sovereignty.

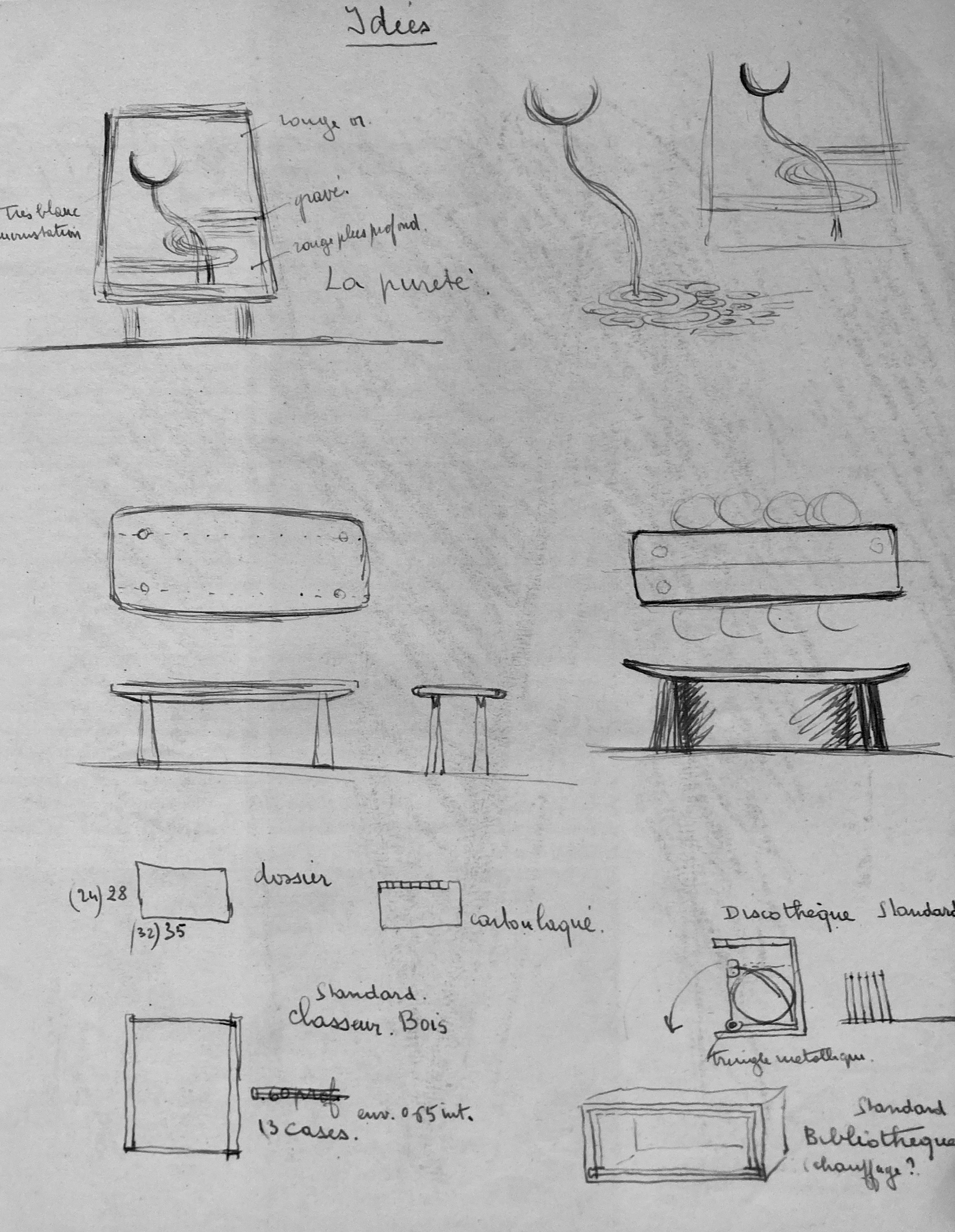

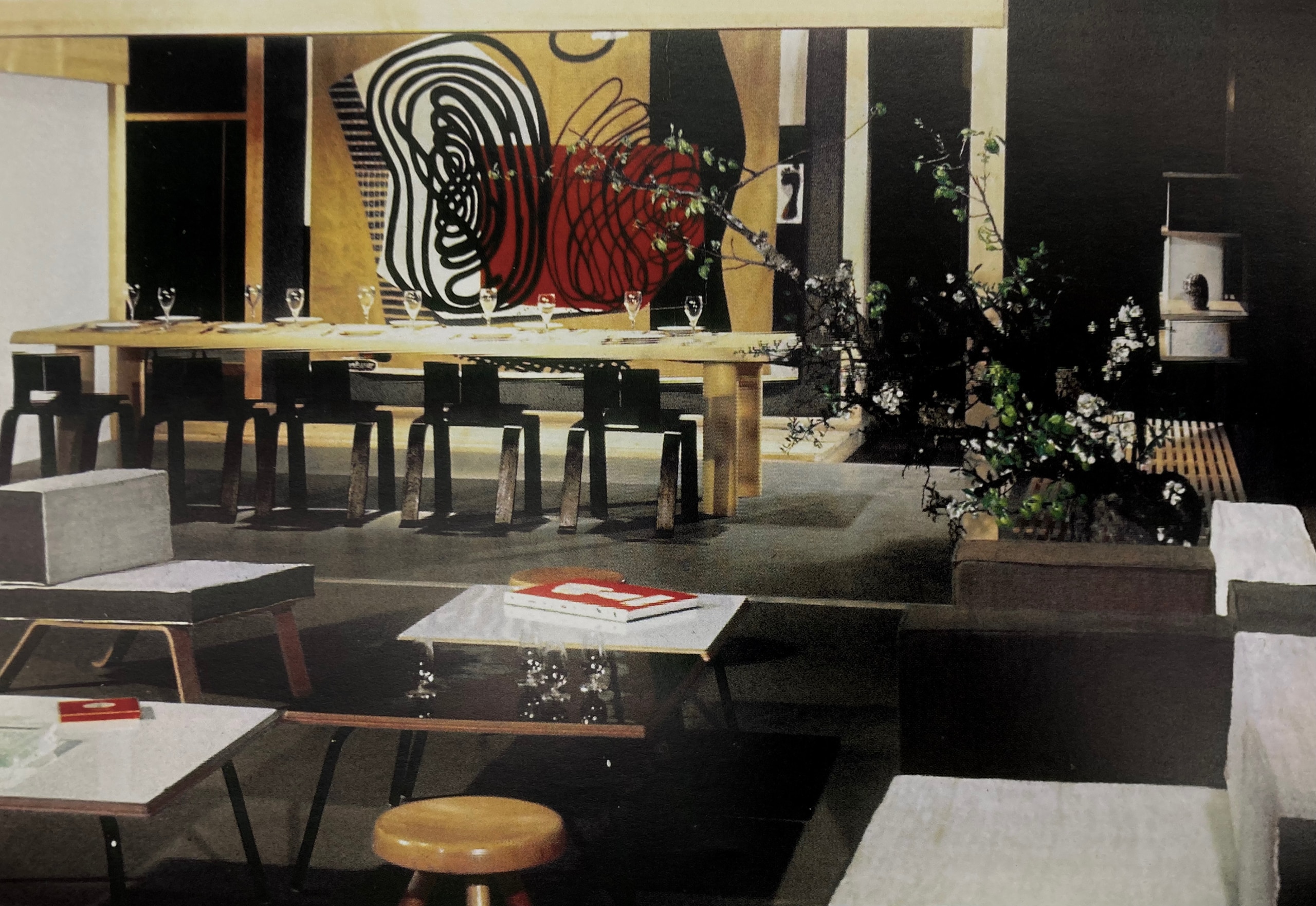

It was in this environment that she returned to Japan in 1953: she firstly found her friends and relatives and she was also there to begun a new traveling exhibition for two years: it was in 1955 that “Pour une synthèse des arts” is finally out, after program changes. The exhibition was a presentation of Japanese furniture and Charlotte Perriand’s ones alongside the works of Joan Miró (1893-1983), Alexander Calder (1898-1976) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) all interacting in a demonstration originally named “The embellishment of life” – a reference from Francis Jourdain (1876-1958). Finally, with the help of the UAM (Union of Modern Artists) and Formes Utiles, only the proponents of European modern art were exhibited and Charlotte Perriand showed full of new creations, as many direct references, both material and poetic, to Japan: “Tokyo” benches, “Nuage” bookcases and “Ombre” chairs; their name coming from the eponymous book, these last ones also draw on shadow theater, bunraku theater and calligraphy.

She wished to exhibit exceptional works and everyday objects and it is clear that she has succeeded, assimilating, integrating and appropriating certain codes of Japanese culture, thus modulating European standardization and modernism. During the exhibition, she also showed her contributions as well as her influences: she used natural materials, proposed modular furniture, played with colors, improved flow, praised the importance of emptiness, reflected on the separation of spaces and their interconnection, integrated certain concepts of feng shui.

Japan: never forget

It is obvious that Charlotte Perriand’s links with Japan are not only geographical: even far away, her transformation is palpable, both philosophically and materially. Here is a proof: after 1940, her creations became more organic and freer; at the end of the World War II, she exhibited this new aesthetic in the most prominent gallery in Saint-Germain-des-Près, Steph Simon, from its opening in 1956. Exhibiting Akari by Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988), Rouleaux by Georges Jouve (1910-1964) and furniture by Jean Prouvé (1901-1984), this fashionable space was one of Charlotte Perriand’s place to spread the Japanese soul and presenting furniture such as the “Butterfly” stool by Sori Yanagi. From near and far, Charlotte Perriand has both friendly and professional ties with Japan. Charlotte Perriand lets her Japanese influences shine through both in the curated interior of the gallery and in her leisure ensembles such as Meribel.

Some of her creations are directly connected to the Land of the Rising Sun. While she designed a Japanese House for the 1957 Salon des Arts Ménagers (SAM) with her friend Sori Yanagi, the commission for the Air France agencies in Tokyo and Osaka in 1959-1960 marked a strong anchor: with the new airline line linking France and Japan now in service, it was obvious to choose the designer to metaphorically materialize this connection, and she chose photos for the display of the ice floe over which the planes fly to underline the material link. In a subtle set between rhythm and purity of space, she arranged icons of post-war design such as the “Tulip” chairs by Eero Saarinen (1910-1961) and the “DSR” and “DAR” seats by Charles (1907-1978) and Ray (1912-1988) Eames.

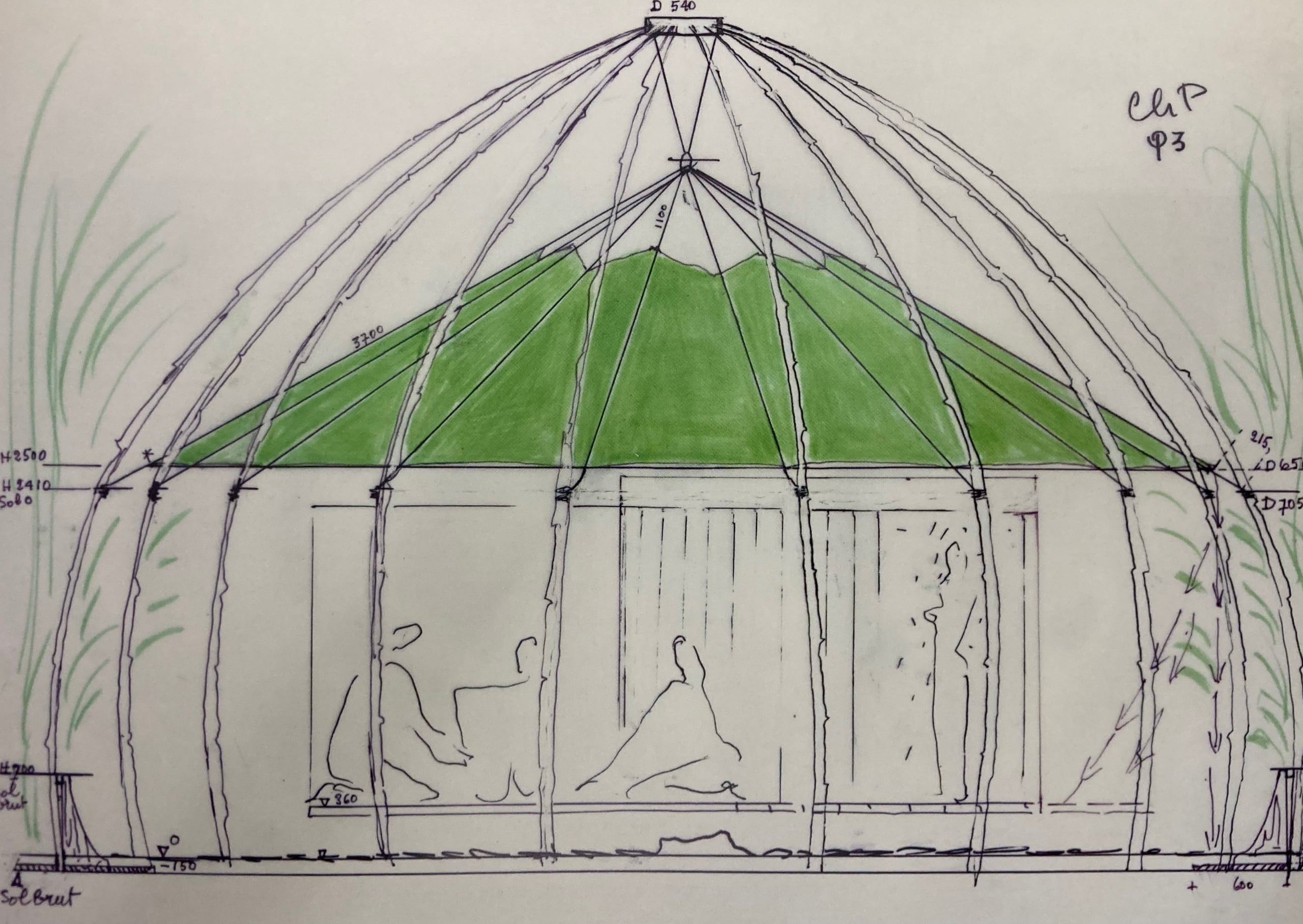

The following decades are equally rich: the minimalism reigning in the apartment of the Japanese ambassador in Paris (1966-1969) for which she worked in close collaboration with her architect friend Junzo Sakakura. This space is perfectly representative with the ideas of adaptability and modularity; Until 1993, with the House of Tea realized for the Parisian headquarters of UNESCO, she played as much on nature as on voids.

Charlotte Perriand’s relationship with Japan can be described as intimate and profound: she selects from tradition to create a new language, thus proceeding to a synthesis of the arts in a permanent game of back and forth, because if she brought her expertise to Japan, the latter transformed her as much as her creations, forever changing her way of understanding spaces and objects. A reciprocity without equivalent. The book “Charlotte Perriand and Japan” by Jacques Barsac (Norma, 2018) analyzed precisely the existing entanglements and clearly underlines this incredible bipartition of influences.

Charlotte Perriand’s travels are essential to understand her personality: if Japan remains undoubtedly the country that has most marked the designer, Brazil is not outdone, and the “Rio” coffee table of 1962 is a good example.