A difficult childhood

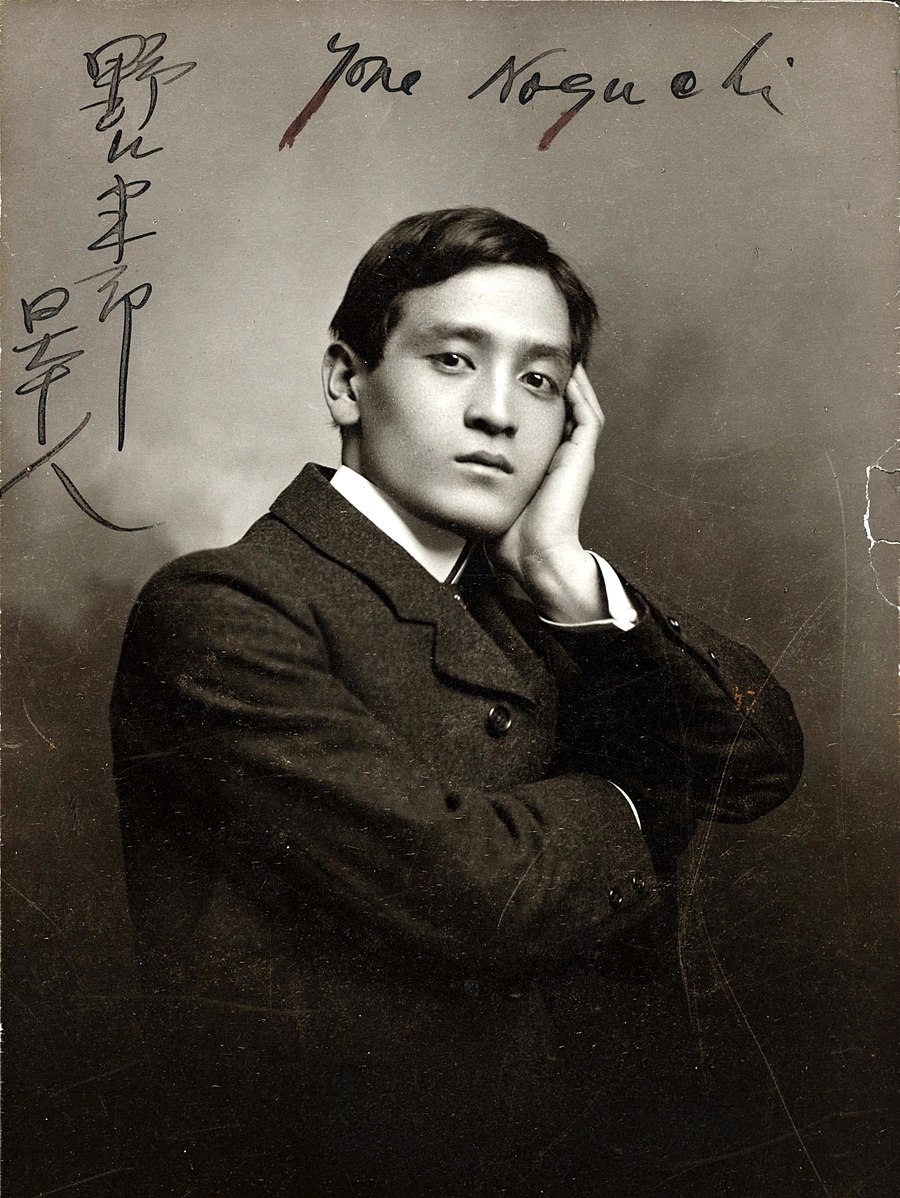

Isamu Noguchi was an undesired child born in Los Angeles on November 17th, 1904. His father, better known in the United States as the poet Yone Noguchi, was born in the center of Japan to a shopkeeper who claimed to descend from a samurai and who had a small store selling wooden sandals, umbrellas, paper and various other items. Yonejirō emigrated to the United States at the age of eighteen and met Noguchi’s American mother, the brilliant Leonie Gilmour, when she interviewed to become his assistant and correct his English texts. Despite a healthy professional relationship, the two young people became involved in a romantic relationship that was entirely dysfunctional. Yone Noguchi made use of Gilmour’s feelings for him to manipulate and exploit her, keeping his liaison with his assistant secret and simultaneously carrying on relationships with various women of influence. From birth, Isamu’s father was absent from his life.

In addition, there was a growing climate of racism towards the Japanese community in America. During the war between Japan and Russia in 1904–1905 the United States had supported Japan, but America took a dim view when, after its victory, Japan began extending its influence beyond its borders, notably in China. It was at this time that numerous anti-Japanese actions and demonstrations began, from daily racism to laws. Furthermore, Leonie Gilmour’s situation was far from easy: Yone Noguchi had abandoned her in a puritan America that regarded single mothers with disapproval, and in addition, the rising current of racism was only going to get worse. It was to escape this context and join the father of her son that she decided to go to Japan: mother and child arrived in Tokyo on March 26th, 1907.

Isamu Noguchi would spend eleven years in Japan, from his childhood years to his early adolescence, a period that is essential in the construction of the future adult one is to become. And these years would profoundly mark him. His father was a shadowy presence at best and, if he did nothing to dissuade mother and son from coming, he had already made a new life for himself. In fact, his very young wife would give birth to the first of their nine children in December 1907. Yonejiro Noguchi visited Leonie and their son from time to time, but he was above all conspicuous by his absence. Leonie Gilmour was terribly alone in a foreign country she didn’t know and where moreover, blood ties and family were of prime importance. Yonejiro Noguchi never officially recognized his son, neither in the United States nor Japan. After living in Tokyo for a while, in 1911 mother and son moved to Chigasaki, a small seaside town village in Kanagawa Prefecture not far from the capital. Leonie had been providing for the family ever since they had arrived in Japan, sometimes without any assistance from Yonejiro Noguchi, and sometimes with a little financial support. She gave private English lessons, before becoming an official English teacher. During her long stay in Japan, she gave birth to a daughter, Ailes, but never revealed the father’s identity. If Leonie Gilmour had gone to Japan to “make her son Japanese”, the reality of his situation was much harsher: although his childhood was happy enough, he was seen as a “gaijin”, a foreigner, and was often rejected by the people he met. The anti-Japanese movement continued to escalate back in America putting Leonie Gilmour in a difficult situation. She was faced with a dilemma: should she stay, or should she go back home? Rejected on the one hand by a country where ethnic background was important and on the other by a country where blood lines were primordial, what place was left for Isamu Noguchi? After eleven years and several difficult episodes, his mother finally decided to send him back to the United States in 1918. If his childhood was marked by an absent father during which his mother was his anchor, she broke part of their bond when she sent him back alone in what was yet another rejection. Noguchi wouldn’t see his mother for five years until she returned with Ailes to live in the United States.

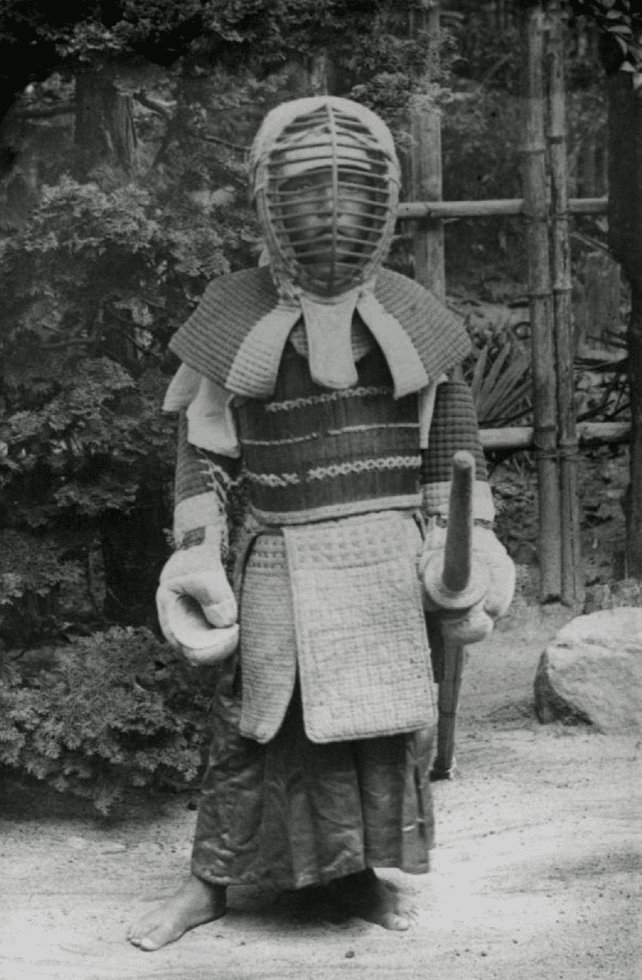

But there were also some positive aspects. During his childhood, Noguchi was immersed in the culture of Japan and its landscapes. He experienced living in a country where art was everywhere and life, governed by age-old traditions, was deliberately calm and gentle: Japanese society was influenced by Zen philosophy, viewing cherry trees in blossom was a beloved pastime and gardens had a sculptural quality. All these impressions and sensations would influence him, deeply.

Name, first name: metonymy of the discord

When he returned to Japan in 1931 following in the footsteps of his past, it was not just to try (in vain) to reestablish contact with his father, but also to try and understand retrospectively some of his emotions and memories, which would be a constant presence and a source of inspiration.

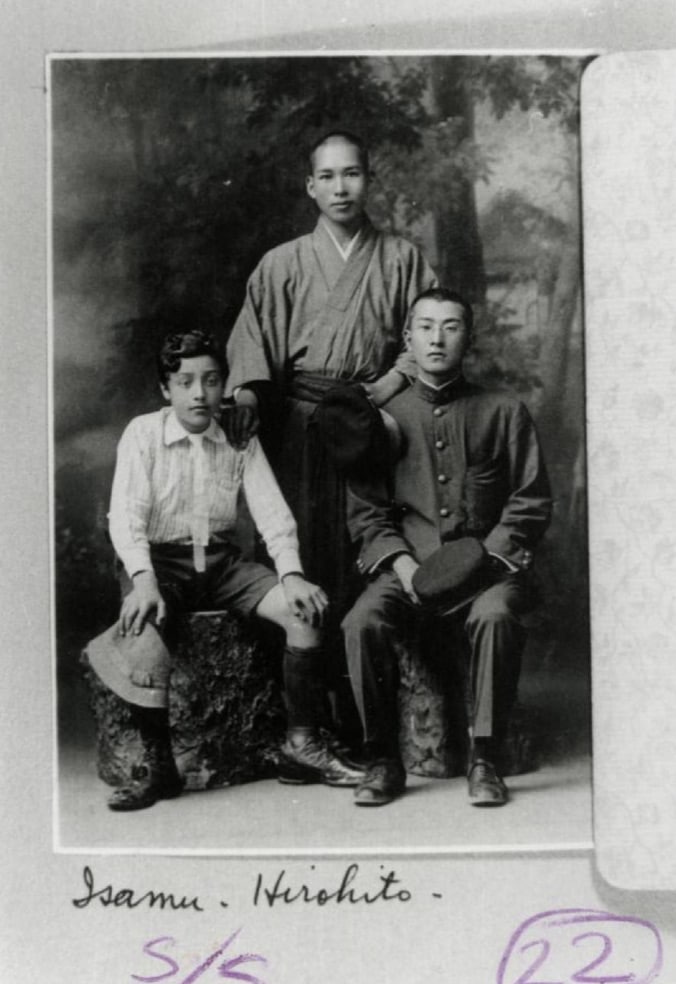

Even Noguchi’s name was a source of conflict. A micro event sheds light (from a metonymical perspective as it were) on these early years marked by antagonistic feelings. In fact, rather than choosing a first name for her son when he was born, Leonie Gilmour waited for his father to express his opinion. When this was not forthcoming, she finally decided to call him Yosemite (after Yo, the diminutive of Yonejiro). He took the name Isamu in Japan, but on his return to America at the age of thirteen, he became known as Sam Gilmour. It was only much later that he decided on Isamu Noguchi, a name that said a lot about his origins and identity. His chosen surname also illustrated just how difficult it was for him to identify with his roots. In fact, his father was opposed to him using the name Noguchi because an illegitimate child was not entitled to bear his father’s name. It was this that ruined his trip to Japan in 1931. The 1910s and 1920s were marked by a growing feeling of resentment towards his father – throughout his life, he looked after a father figure, at this time, Docteur Rumely who was taken him in – and father and son corresponded irregularly in impersonal letters that wavered between interest and scorn. In 1930, Isamu Noguchi decided to go to Asia and visit China and India, before returning once again to the land of his father’s birth. However after setting off on his pilgrimage, he received a letter from his mother telling him that his father did not want him to come to Japan if he was using the name “Noguchi”. Another heartbreak. Noguchi travelled to Japan nonetheless – at a time when the nationalist movement was gaining momentum- and finally had a short meeting with Yonejiro Noguchi.

His father had died in 1947 and although during his lifetime his strained and complex relationship with his son had meant any bond was almost inexistent, now Isamu Noguchi wanted to find a connection and every visit was undertaken in a spirit of reconciliation and as a tribute to his memory.

1950, a journey of reconciliation

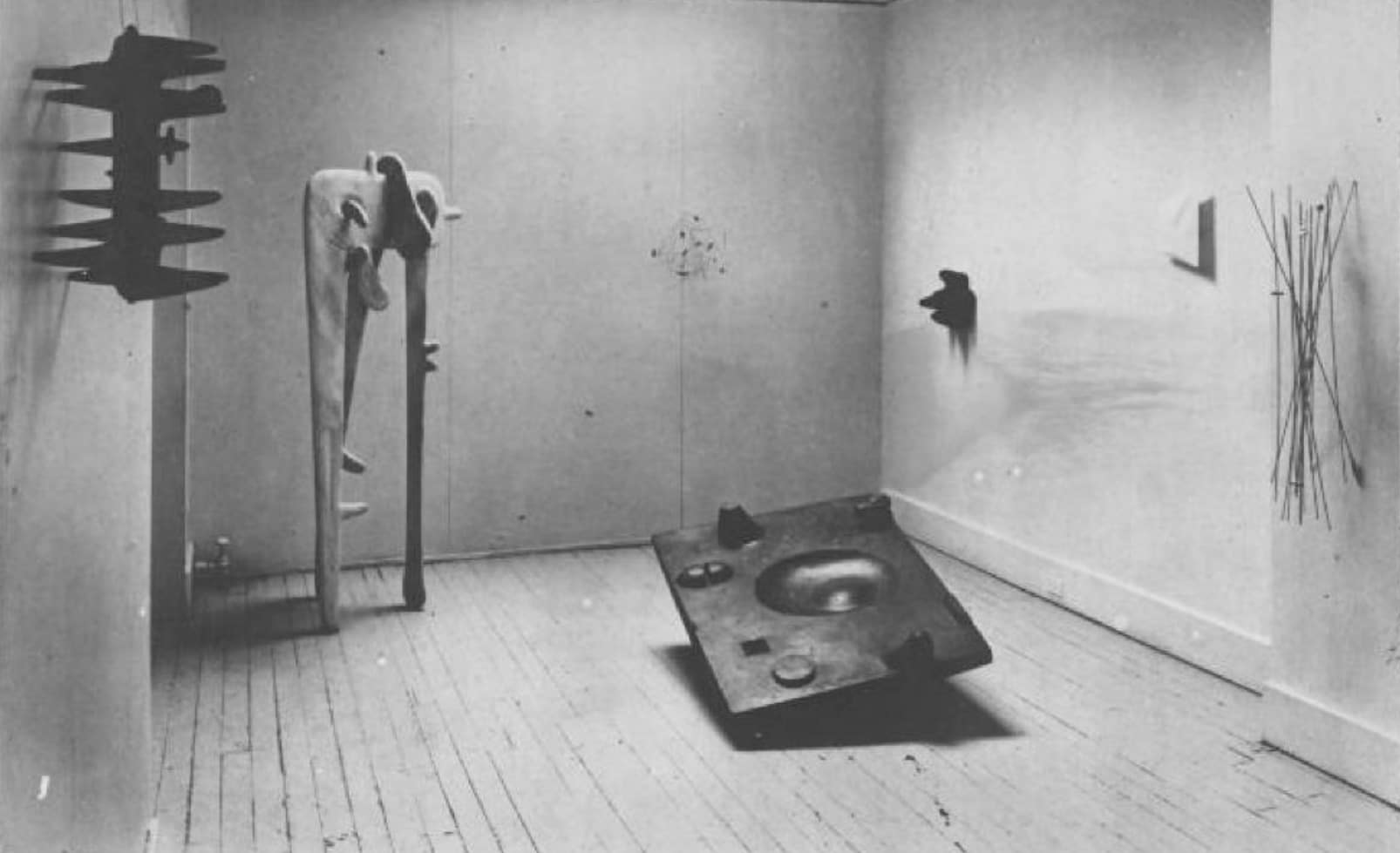

This voyage came after the suicide of his friend, the naturalized Armenian American painter Arshile Gorky (born in 1904) on July 21st, 1948. Noguchi felt the need to get away, to get away from New York where he was constantly reminded of “his dear friend”, and to get away from an art scene that he found increasingly nauseating. Following this tragic event amidst a myriad of others, in 1948 he applied to the Bollingen Foundation for a travel fellowship. It was only however after his exhibition at the Charles Egan Gallery in March 1949 that he finally got away: “After the elation and effort that go with preparing an exhibition, comes depression […] I was determined to get away from everything.”

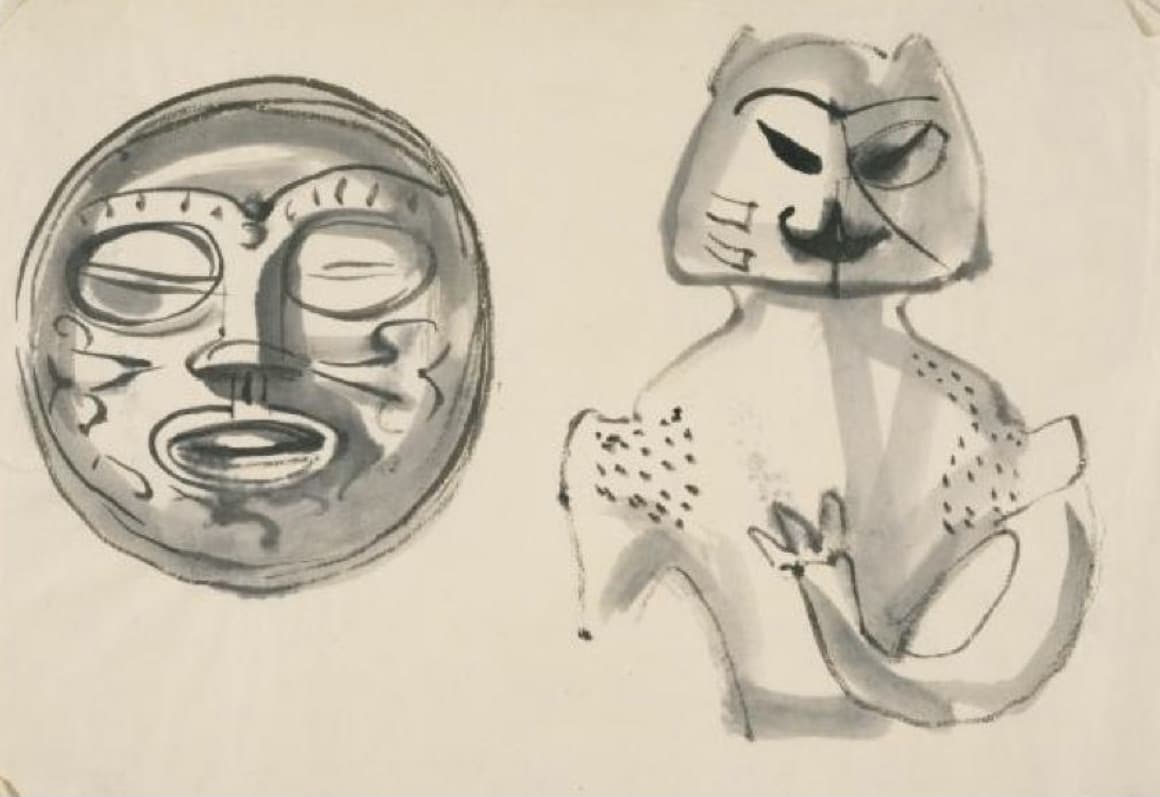

On March 30th, 1949, his application was finally accepted. He flew to Paris on May 12th, 1949 from where he would begin his travels. The idea was to continue research for his book the study of “Leisure”, but what he really wanted was to study and understand the role of sculpture in society and its relationship to the perception of space, which was a leitmotif in both his life and art. He roamed successively across France, England, Italy, Greece, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Thailand and Cambodia, visiting major historical, mystical and artistic sites. On May 2nd, 1950 he arrived in Japan, the ultimate stage of his journey, where he would stay for four months.

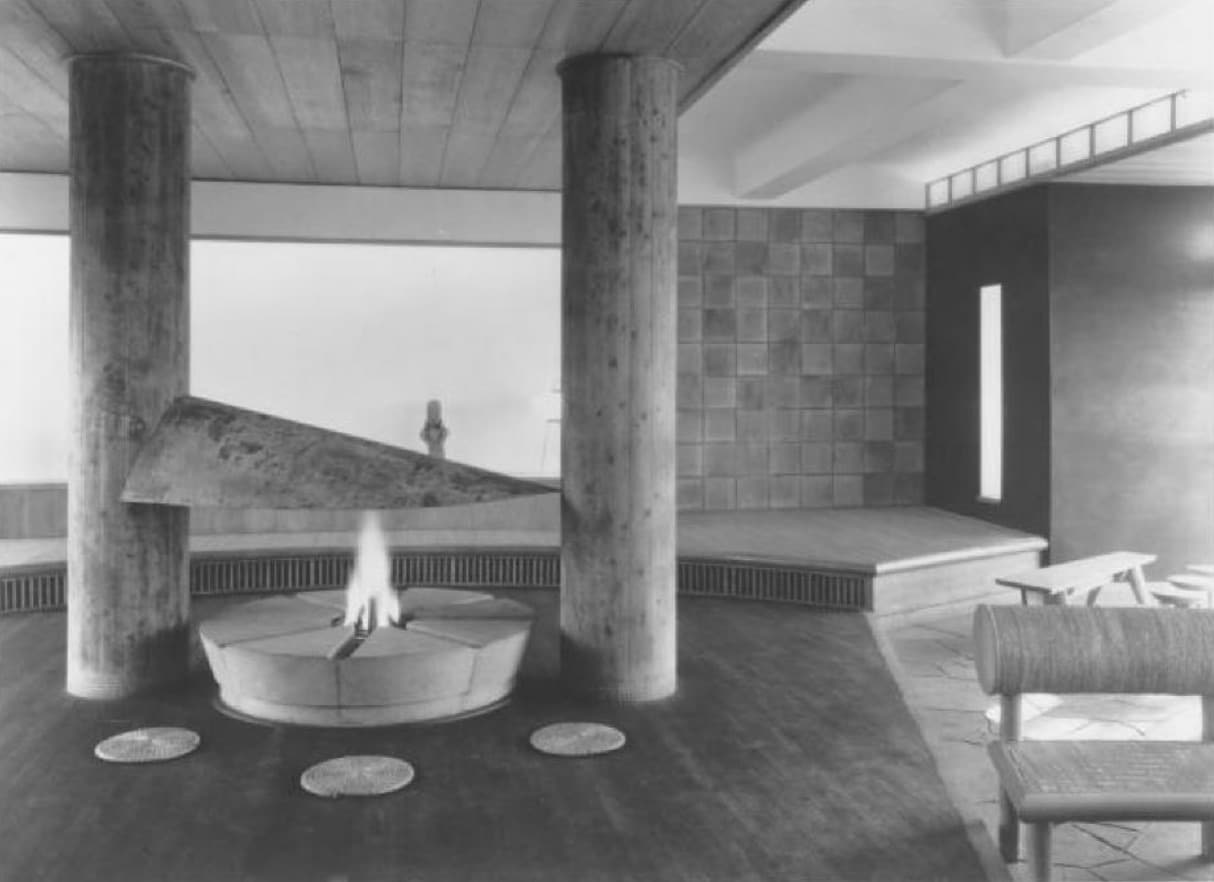

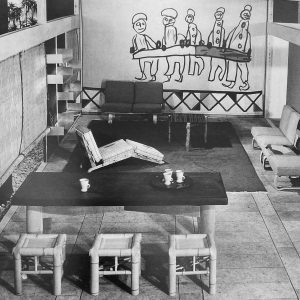

Receiving the welcome he deserved as a renowned artist, Noguchi embarked upon a series of conferences and lectures, traveled to various sites, met with artists and people from the world of industry, worked with Japanese designers and carried out commissions for prestigious institutions. There was a symbolic dimension to the triumphal return of the Japanese American artist. At that time, Japan was still under the domination of the United States following its defeat in WWII and so, in the person of Isamu Noguchi, the country was welcoming both a representative of the occupying forces and a native son come home. His first commission was for the Shinbanraisha at Keio University in Tokyo, where Yone Noguchi had taught for more than forty years. The university campus was being rebuilt after the trials and tribulations. Isamu Noguchi answered the commission in a most sculptural manner, a concept that informed every field of his creative practice and an aspect that Yoshiro Taniguchi (1904–1979), the architect in charge of the building work, particularly admired. From the central seating area with its curved benches to Mu, his famous sculpture, the entire project is an ode to reconciliation, both from a formal and conceptual viewpoint, and a genuine memorial to his father. Its convivial and relaxing atmosphere made it the perfect place to meet and contemplate the ideal of beauty that Yonejirō Noguchi expressed in his poems.

This was followed by a proposition to design railings for two bridges in the new Peace Park on the site of Hiroshima, which came about after his exhibition at Mitsukoshi Department Store in August 1950 towards the end of his stay. Amongst the ceramics, the plans and models for his first hall project and furniture made at the Industrial Arts Research Institute in Tokyo with Isamu Kenmochi (1912-1971), Isamu Noguchi had also presented a project for a tower in Hiroshima. At that time, part of the site of the atomic bombing was being rebuilt to create the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park and deeply moved by this event, Noguchi wanted to play his part. The city’s mayor Shinzo Hamai, together with the renowned Japanese architect in charge of the park, Kenzo Tange (1913-2005), were both impressed by Noguchi’s Bell Tower for Hiroshima. Without responding favorably to the proposed construction, the two men invited him to design the railings for the Peace Bridge, which consists of an eastern and western bridge: Ikiru (To Live) and Shinu (To Die) – which were later renamed Tsukuru (To Build) and Yuku (To Depart).

Isamu Noguchi has finally left his mark on a his half-blood-country.

“With my double nationality and double upbringing where was my home? Where my affections? Where my identity? Japan or America, either, both – or the world?”: Isamu Noguchi’s words in A Sculptor’s World (New York, Harper and Row, 1968) are perfectly clear.

Between the mixed fortunes of his childhood and this trip that left a bitter taste in his mouth, Noguchi’s relationship with Japan was conflicting to say the least. This country symbolized his father and, as such, was the material and geographical representation of the feelings of rejection and abandon that were a fundamental part of his life.

At the end of this rich journey, Noguchi returned to the United States on September 5th, 1950, however the connection that he had forged with Japan and the projects that were set in motion during his stay led him to return not long after in March 1951. This new visit saw the birth of Akari.